Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are common. Many Tribal individuals, families, and communities have been impacted by childhood experiences causing physical and mental health adversities throughout the lifespan. This Information Hub includes brief education and resources to increase awareness and knowledge of ACEs and will increase Indian Country's capacity to address these adversities.

This Information Hub is the result of a partnership between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Indian Health Board (NIHB). This Hub includes a "resource basket" designed for AI/AN individuals, families, communities, professionals, and leaders to rummage through, harvesting resources. This Hub can assist Tribes to learn more about ACEs, research, tools, and interventions. Additionally, NIHB plans to continue weaving into the basket, adding more resources and building on this resource in the future.

The Hub contains the following sections:

Background Information on ACEs

A Word on the Content, Hope, and Healing

How are ACEs Relevant to Me?

ACE Assessments

Success Story

Resource Basket for American Indian and Alaska Native Communities

Peer-Reviewed Articles about ACEs and AI/ANs

How Communities are Adapting and Integrating Research Findings

General ACE Resources

Accessible Tools used in Peer-Reviewed AI/AN Research

ACE Trainings

This resource was developed through the support from a cooperative agreement between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Indian Health Board (CDCOT18-1802, Grant #NU38OT000302). The findings and conclusions presented in this resource are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the U.S. government.

For more information about the ACES Information Hub, contact Courtney Wheeler, [email protected], 202-507-4081.

Mary grew up one of three children. Her father was an alcoholic and her mother suffered from depression. They lived in a remote area on a reservation and where there were few opportunities. Both parents struggled with finding and keeping employment and the family was very poor. Sometimes, there was not enough money to buy food or heat their home. Because her parents were sick, they sometimes did not take adequate care of the children, leaving Mary with no attention, care, or support. Mary and her siblings were often bullied by classmates. Because of all these issues, Mary had trouble paying attention in school so she often earned poor grades and got into fights. When she got in trouble at school, her father sometimes hit her. When Mary was in middle school, her mother attempted suicide. Fortunately, she recovered, but Mary's family was deeply affected and her dad left. This story is a fictional example, but reflects realities that many American Indian/Alaskan Natives experience.

How many of us have been affected by suicide? Divorce? Violence at home? Substance abuse? Poverty? Lack of opportunities? In Western society, these experiences are commonly described as ACEs, or Adverse Childhood Experiences.

The health impacts of ACEs first came to light during a groundbreaking study conducted by the CDC and Kaiser Permanente between 1995 and 1997. This study identified relationships between the breadth of the exposure to abuse or household challenges during childhood and multiple risk factors for several of the leading causes of death in adults (Felitti, Anda, & Nordenberg, 1998). This study is known as the Adverse Childhood Experiences study.

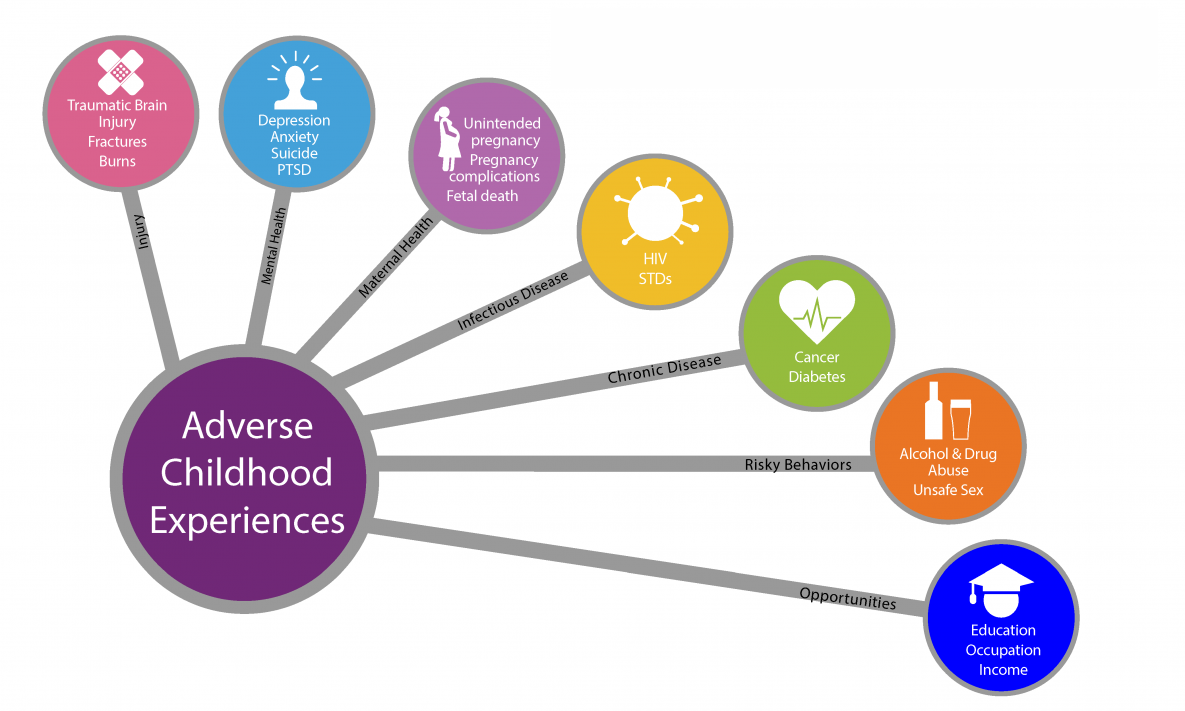

ACEs are potentially traumatic events occurring during childhood (from the ages of 0 to 17) such as experiencing violence, abuse, or neglect; witnessing violence in the home; and having a family member attempt or die by suicide. ACEs also include aspects of a child's environment that can undermine their sense of safety, stability, and bonding such as growing up in a household with substance misuse, mental health problems, or instability due to parental separation or incarceration of a parent, sibling, or other member of the household. Some of the research or resources below also consider other types of ACEs, including historical trauma, bullying, and discrimination. Many AI/AN people have experienced these impacts, even though they are not considered in most traditional, mainstream ACE questionnaires. Adverse Childhood Experiences have been linked to risky health behaviors, chronic health conditions, low life potential, mental health and poor behavioral health outcomes, and early death. As the number of ACEs increases, so does the risk for these outcomes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019).

The graphic below shows some of the health consequences of ACEs.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019.

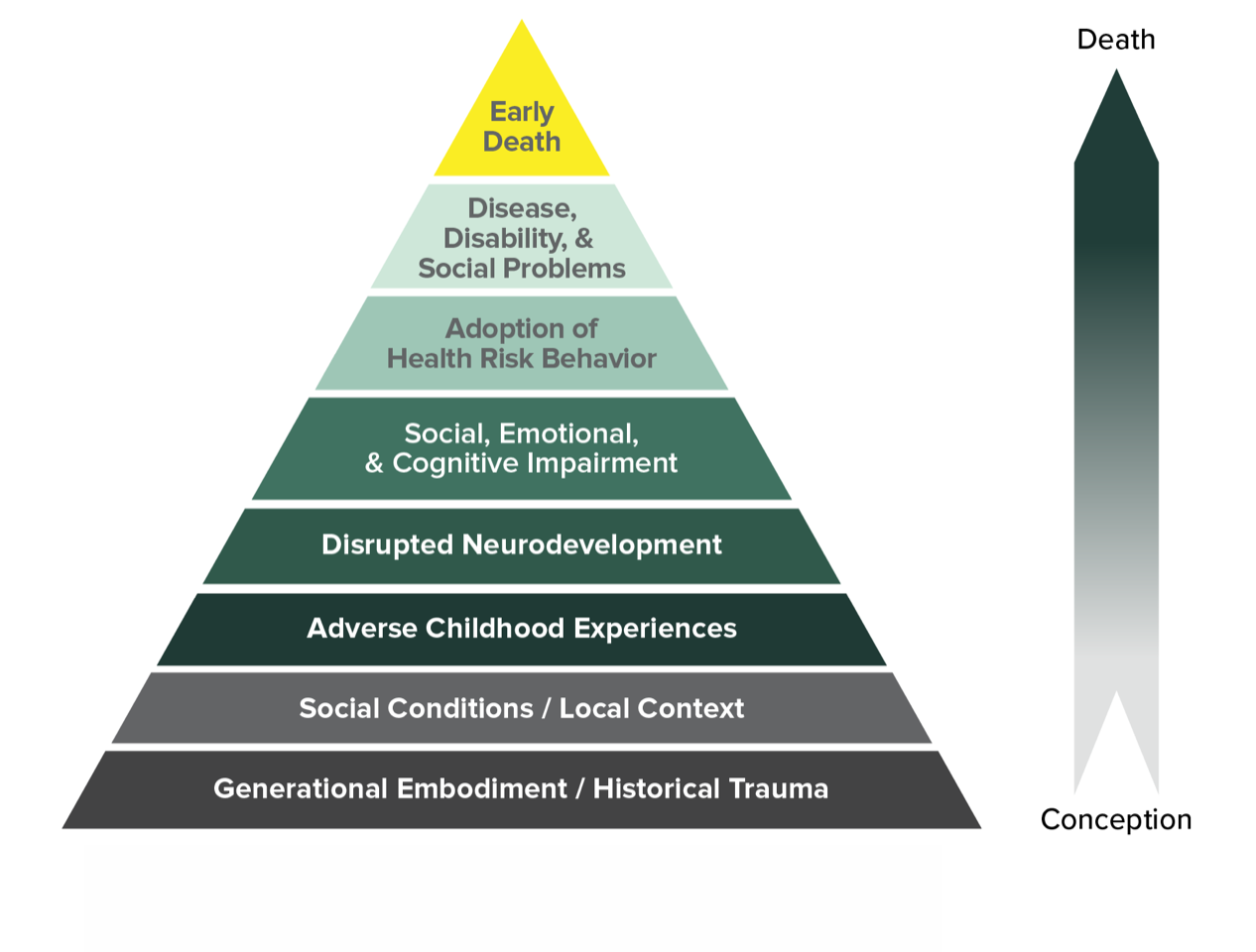

In addition to experiencing a greater burden of health disparities compared to other Americans, AI/AN people also experience ACEs disproportionately. These health disparities may result from social determinants of health including inadequate education, poverty, and lack of healthcare, but ACEs are implicated as well. ACEs have been shown to affect health and wellbeing in the general population and have likely impacted AI/AN of all ages in ways researchers are only now beginning to understand. The image below shows the general mechanism for how ACEs impact health and wellbeing during an individual's life

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019.

A similar pyramid was published as part of the original ACEs study and there have been several different adaptations, including the one shown above designed by the RYSE Center.

Since 1998, many researchers have used the ACE survey to explore the influence and impact of these experiences on a range of health conditions and populations; however, few of these studies have focused on effects of ACEs within AI/AN populations.

The information hub compiles/organizes known resources about ACEs and AI/AN to share information about the work done to date and making findings, instruments, and recommendations easily available for use.

Most research on ACEs has come from outside of indigenous communities using

mainstream American values, standards, definitions, and lenses. Therefore,

ACEs and ACE interventions in Tribal communities may be different. This Hub

contains information on how Tribes are using and implementing work with

ACEs. In the future, there may be opportunities to indigenize the framework

itself-including the pyramid above, the ACE assessment, and other ACE

information to better fit

AI/AN populations. This ACE information can be considered foundational and

adapted as appropriate to different groups; for example, traditional

studies may not have yet shown the impact of inadequate housing as an ACE,

but it may still have similar impacts and be relevant to your community.

Below are 2 examples of indigenizing ACEs for Tribal communities . See the Peer-Reviewed Articles about ACEs and AI/ANs section for more examples.

This Information Hub and the resources below use candid language to discuss the important topics with the hope that addressing these issues frankly will benefit AI/AN communities. However, this content may be disturbing to people, especially (but not only) those who have directly experienced ACEs.

It is important to understand that the consequences of ACEs are not inevitable-experiencing ACEs does not destine someone for a life of pain or illness. It is not fate that someone will suffer or will not heal from the effects of ACEs. Although ACEs can be used to highlight health risks for individuals and populations overall, many happy, healthy, and successful people have experienced ACEs. Additionally, seeking treatment can combat ACEs' effects on individuals and break the cycle for themselves and their children. It is never too late to get help. It is also worth noting that ACE questionnaires do not typically consider positive factors such as resilience and support or the overall impact of ACEs on any one individual. In other words, an ACE score is an indicator of what happened to a person, not an absolute indicator of how someone functions now or even how ACEs affected or might affect him or her. Understanding this can turn an ACE score into something productive-a way to better understand oneself, one's health, and one's health risks in order to lead a healthy life.

If you find the content here upsetting, please consider seeking help. Primary care providers are able to provide treatment or referrals for trauma and other mental/behavioral health problems related to ACEs. Local resources such as counseling, substance misuse support, and psychiatry may also be available.

The following helplines may be useful. Most are available 24 hours a day and many offer phone, text, and online chat options.

In most of the United States, dialing 211 on a phone will reach a referral service connecting individuals to resources addressing a variety of different needs. This service is not available in all areas.

As always, call 911 or your local emergency number if you are in immediate danger.

ACEs are relevant to individuals, family and community members, and people in a variety of different occupations and roles.

People Who Have Experienced ACEsPeople who have experienced ACEs should be aware of their effects so they can seek appropriate health care when needed. They can also get professional and social support to improve their lives and avoid allowing ACEs to impact their children, families, and futures. Some ACE survivors find they understand themselves better after learning about ACEs and considering their own experiences. |

Healthcare ProvidersHealthcare providers of all types including traditional practitioners, physicians, nurse practitioners, midwives, nurses, and others-should understand ACEs and their impacts on physical and mental health. This information can help them understand and help their patients efficiently and make appropriate referrals and screenings. |

Social Workers and Community Health WorkersSocial workers and community health workers can use ACE knowledge to better help their clients, screening for ACEs when appropriate and providing support and referrals. ACEs can also help explain ongoing client challenges, trauma, behavioral challenges, and repeating cycles of violence. |

Teachers and Others Working with ChildrenTeachers and others who work with children are sometimes the first and only individuals outside of a family to recognize when children are currently experiencing ACEs. They can provide initial support and referrals to help the children and their families. Understanding ACEs can also help teachers and others better understand their children's challenges, behaviors, and needs. |

Family and Community MembersPeople who have family members, friends, community members, or coworkers who have experienced ACEs can offer support and help address needs. Sometimes, they can be the first to identify that someone is having problems or needs help. Understanding ACEs can also help people become more patient, offer support and assistance, and prevent further damage. |

Tribal LeadersTribal leaders should know about ACEs to help understand and support their communities and include ACEs in decision making. |

Policy MakersPolicy makers and related experts should understand ACEs to allocate funding to address these needs. |

Law EnforcementLaw enforcement staff and others in related roles can use ACE knowledge to efficiently serve their communities. Understanding challenges can help them recognize and address special needs and prioritize support to physical and mental health care services and rehabilitation. |

EveryoneEveryone should know about ACEs! Their impact on individuals and on our communities is important. |

No credentials are needed to administer an ACE's questionnaire. Any provider can use ACEs and ACE tools to make a difference for clients. However, it IS important to know how to respond and have the appropriate skills and resources to follow up. It can be emotional, difficult, or painful for clients to disclose their ACE scores, especially if also sharing details of lived trauma, and clients may feel there is risk involved. Disclosing clients deserve appropriate follow-up and should never feel their issues or calls for help were ignored, left unaddressed, or mishandled. For example, ignoring a disclosure on an intake form, responding in a way that could seem judgmental (such as asking probing questions), or not providing appropriate resources and support in follow-up, could make the client feel worse. It is important for any staff to have appropriate training and a clear response plan in place. Many of the resources below provide support on responding to ACE disclosures.

There are different assessments used to screen for ACEs. Below, you can see the original ACE questions used in the first study and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) questions currently used by the CDC. These questionnaires are most standardly used.

|

Original ACES |

Original BRFSS Question |

|

|

Introduction |

Obtained the questions from a table developed by Coordinated Core Services, Inc., www.ccsi.org. |

I'd like to ask you some questions about events that happened during your childhood. This information will allow us to better understand problems that may occur early in life, and may help others in the future. This is a sensitive topic and some people may feel uncomfortable with these questions. At the end of this section, I will give you a phone number for an organization that can provide information and referral for these issues. Please keep in mind that you can ask me to skip any question you do not want to answer. All questions refer to the time period before you were 18 years of age. Now, looking back before you were 18 years of age--, |

|

Lifetime prevalence of emotional abuse |

Did a parent or other adult in the household often or often swear at you, insult you, put you down or humiliate you? Or ever act in any way that made you afraid that they might physically hurt you? [yes/no] |

How often did a parent or adult in your home ever swear at you, insult you, or put you down? Was it…

|

|

Lifetime prevalence of physical abuse |

Did a parent or other adult in the household often or very often push, grab, slap or throw something at you? Or ever hit you so hard that you had marks or were injured? [yes/ no] |

Not including spanking, (before age 18), how often did a parent or adult in your home ever hit, beat, kick, or physically hurt you in any way? Was it-

|

|

Lifetime prevalence of sexual abuse |

Did an adult or person at least 5 years older than you ever touch or fondle you or have you touch their body in a sexual way or attempt to, or have sex with you? [yes/ no] |

How often did anyone at least 5 years older than you or an adult, ever touch you sexually? Was it…

How often did anyone at least 5 years older than you or an adult, try to make you touch them sexually? Was it…

How often did anyone at least 5 years older than you or an adult, force you to have sex? Was it…

|

|

Lifetime prevalence of physical neglect |

5. Did you often or very often feel that you didn't have enough to eat, had to wear dirty clothes, or had no one to protect you or your parents were too drunk or high to take care of you or take you to the doctor if needed? [yes/no] |

For how much of your childhood was there an adult in your household who tried hard to make sure your basic needs were met? Would you say never, a little of the time, some of the time, most of the time, or all of the time?

|

|

Lifetime prevalence of emotional neglect |

4. Did you often or very often feel that no one in your family loved you or thought you were special, or your family didn't look out for each other, feel close to each other or support each other? [yes/no] |

For how much of your childhood was there an adult in your household who made you feel safe and protected? Would you say never, a little of the time, some of the time, most of the time, or all of the time?

|

|

Lifetime prevalence of witnessed intimate partner violence |

Was your mother or stepmother often or very often pushed, grabbed, slapped or had something thrown at her? Or sometimes, often, or very often kicked, bitten hit with a fist, or hit with something hard, or ever repeatedly hit for at least a few minutes, or threatened with a gun or a knife? [yes/no] |

How often did your parents or adults in your home ever slap, hit, kick, punch or beat each other up? Was it…

|

|

Lifetime prevalence of household substance abuse |

Did you ever live with someone who was a problem drinker or alcoholic or used street drugs? [yes/no] |

Did you live with anyone who was a problem drinker or alcoholic?

Did you live with anyone who used illegal street drugs or who abused prescription medications?

|

|

Lifetime prevalence of household mental illness |

Was a member of your household depressed, mentally ill or did a household member attempt suicide? [yes/ no] |

Did you live with anyone who was depressed, mentally ill, or suicidal?

|

|

Lifetime prevalence of incarcerated relative |

Did a household member ever go to jail or prison? [yes/no] |

Did you live with anyone who served time or was sentenced to serve time in a prison, jail, or other correctional facility?

|

|

Were your parents ever divorced or separated? [yes/ no] |

Before you were 18 years of age, were your parents married, never married, separated, or divorced?

|

Mary, from our story in the introduction, learned about ACEs from a maternal/early childhood home visitor working on her reservation.

At first,discussing ACEs was difficult and overwhelming. Mary worried greatly about how ACEs had impacted her life and might continue to impact her future and her young daughter. Mary spoke to her primary care doctor about her stress. Her provider completed an assessment, identified and treated problems, and minimized impacts to Mary's health. Mary was also able to work through her traumas and process feelings during therapy with a mental health provider. She identified ways ACEs had impacted her wellbeing.

With help and support, Mary was able to make positive changes in her life and help protect her child. Mary is now able to live a balanced and healthy lifestyle by prolonging her lifespan to carry on her traditions since she got help—all because she took the ACEs assessment.

Coming soon!

This section contains a wealth of articles, tools, and other resources relevant to American Indians/Alaska Natives and ACEs.

View each section below to learn more.

This section describes peer-reviewed articles about American Indians/Alaska Natives and ACEs. Topics include alcohol dependence, behavioral health, chronic disease, incarceration, and violence.

Adverse Childhood Exposure and Alcohol Dependence Among Seven Native American Tribes

Koss, M. P., Yuan, N. P., & Dightman, D. (2003). Adverse childhood exposures and alcohol dependence among seven Native American tribes. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 25(3), 238-244.

Article Summary

Background: Alcohol abuse and alcoholism are leading causes of death among Native Americans. Little is known about the impact of negative childhood exposures, including parental alcoholism, childhood maltreatment, and out-of-home placement, on risk of lifetime DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition) diagnosis of alcohol dependence in this population.

Methods: Face-to-face interviews were conducted with 1660 individuals from seven Native American tribes from 1998 to 2001. Logistic regression was used to estimate the impact of specific types and number of different adverse childhood experiences on alcohol dependence. Relationships between tribe-specific cultural characteristics and alcohol dependence were also examined.

Results: There were significant tribal differences in rates of alcohol dependence and several adverse childhood exposures. Lifetime prevalence of alcohol dependence was high among all tribes (men: 21%-56%, women: 17%-30%), but one (men: 1%, women: 2%). High prevalence rates were documented for one or more types of adverse childhood experiences (men: 74%-100%; women: 83%-93%). For men, combined physical and sexual abuse significantly increased the likelihood of subsequent alcohol dependence (odds ratio [OR]=1.58; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.10-2.27). For women, sexual abuse (OR=1.79; 95% CI, 1.21-2.66) and boarding school attendance increased the odds of alcohol dependence (OR=1.57; 95% CI, 1.03-2.40). Two separate patterns of dose-response relationships were observed for men and women. Significant inter-tribal differences in rates of alcohol dependence remained after accounting for tribe-specific cultural factors and geographic region.

Conclusions: Effects of childhood exposures on high-risk behaviors emphasize screening for violence in medical settings and development of social and educational programs for parents and children living on and near tribal reservations.

The Impact of Stressors on Second Generation Indian Residential School Survivors

Bombay, A., Matheson, K., & Anisman, H. (2011). The impact of stressors on second generation Indian Residential School survivors. Transcult Psychiatry, 48(4), 367-391. doi:10.1177/1363461511410240

Article Summary

From 1863 to 1996, many Aboriginal children in Canada were forced to attend Indian Residential Schools (IRSs), where many experienced neglect, abuse and the trauma of separation from their families and culture. The present study examined the intergenerational impact of IRS exposure on depressive symptomatology in a convenience sample of 143 First Nations adults. IRS experiences had adverse intergenerational effects in that First Nations adults who had a parent attend IRS (n = 67) reported greater depressive symptoms compared to individuals whose parents did not attend (n = 76). Parental IRS attendance moderated the relations between stressor experiences (adverse childhood experiences, adult traumas, and perceived discrimination) and depressive symptoms, such that second-generation Survivors exhibited greater symptomatology. Adverse childhood experiences partially mediated the relation between parental IRS attendance and both adult trauma and perceived discrimination. Moreover, both of these adulthood stressors partially mediated the relation between adverse childhood experiences and depressive symptoms. Finally, all three stressors demonstrated a unique mediating role in the relation between parental IRS attendance and depressive symptoms. Although alternative directional paths could not be ruled out, offspring of IRS survivors appeared at increased risk for depression, likely owing to greater sensitivity to and experiences of childhood adversity, adult traumas, and perceived discrimination.

A Framework to Examine the Role of Epigenetics in Health Disparities among Native Americans.

Brockie, T. N., Heinzelmann, M., & Gill, J. (2013). A framework to examine the role of epigenetics in health disparities among Native Americans. Nursing Research and Practice, 2013, 9. doi: 10.1155/2013/410395

Article Summary

Background: Native Americans disproportionately experience adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) as well as health disparities, including high rates of posttraumatic stress, depression, and substance abuse. Many ACEs have been linked to methylation changes in genes that regulate the stress response, suggesting that these molecular changes may underlie the risk for psychiatric disorders related to ACEs.

Methods: We reviewed published studies to provide evidence that ACE-related methylation changes contribute to health disparities in Native Americans. This framework may be adapted to understand how ACEs may result in health disparities in other racial/ethnic groups.

Findings: Here we provide evidence that links ACEs to methylation differences in genes that regulate the stress response. Psychiatric disorders are also associated with methylation differences in endocrine, immune, and neurotransmitter genes that serve to regulate the stress response and are linked to psychiatric symptoms and medical morbidity. We provide evidence linking ACEs to these epigenetic modifications, suggesting that ACEs contribute to the vulnerability for developing psychiatric disorders in Native Americans.

Conclusion: Additional studies are needed to better understand how ACEs contribute to health and well-being. These studies may inform future interventions to address these serious risks and promote the health and well-being of Native Americans.

Brockie, T.N., Dana-Sacco, G., & Wallen, G. R. (2015). The relationship of adverse childhood experiences to PTSD, depression, poly-drug use and suicide attempt in reservation-based Native American adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55(3-4), 411-421.

Article Summary

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are associated with numerous risk behaviors and mental health outcomes among youth. This study examines the relationship between the number of types of exposures to ACEs and risk behaviors and mental health outcomes among reservation-based Native Americans. In 2011, data were collected from Native American (N = 288; 15-24 years of age) tribal members from a remote Plains reservation using an anonymous web-based questionnaire. We analyzed the relationship between six ACEs, emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, physical and emotional neglect, witness to intimate partner violence, for those under 18 years, and included historical loss associated symptoms, and perceived discrimination for those over 19 years; and four risk behavior/mental health outcomes: post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, depression symptoms, poly-drug use, and suicide attempt. Seventy-eight percent of the sample reported at least one ACE and 40 % reported at least two. The cumulative impacts of the ACEs were signi?cant (p\.001) for the four outcomes with each additional ACE increasing the odds of suicide attempt (37 %), poly-drug use (51 %), PTSD symptoms (55 %), and depression symptoms (57 %). To address these ?ndings culturally appropriate childhood and adolescent interventions for reservation-based populations must be developed, tested and evaluated longitudinally.

Childhood Sexual Abuse and Depression among American Indians in Adulthood

Easton, S. D., Roh, S., Kong, J., Lee, Y-S.(2019). Childhood sexual abuse and depression among American Indians in adulthood. Health & Social Work, 44(2), 95-103. doi:10.1093/hsw/hlz005

Article Summary

The present study investigated distal and proximal factors associated with depression among a sample of 479 American Indian (AI) adults in the Midwest. Distal factors included histories of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) and other childhood adversities. Proximal factors included levels of health self-efficacy and treatment for alcohol problems. The study also examined the moderating effect of treatment for alcohol problems on the relationship between CSA and depression. In model 1, results indicate that CSA was positively related to depression after controlling for demographic and background variables. In model 2, childhood adversities and treatment for alcohol problems were associated with increased depression in AI adults; CSA became nonsignificant. As a protective factor, level of health self-efficacy was negatively associated with depression. In model 3, treatment for alcohol problems magnified the effect of CSA depression. These findings suggest that early traumatic experiences may have persistent, harmful effects on depression among AIs; one mechanism exacerbating the impact of CSA on depression is treatment for alcohol problems. Targeted interventions are needed to mitigate the long-term negative health effects of childhood trauma in this population and to strengthen proximal protective factors, such as health self-efficacy.

Kenney, M. K., & Singh, G. K. (2016). Adverse childhood experiences among American Indian/Alaska Native children: The 2011-2012 National Survey of Children's Health. Scientifica, 2016, 14. doi:10.1155/2016/7424239

Article Summary

We examined parent-reported adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and associated outcomes among American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) children aged 0-17 years from the 2011-2012 National Survey of Children's Health. Bivariate and multivariable analyses of cross-sectional data on 1,453 AI/AN children and 61,381 non-Hispanic White (NHW) children assessed race-based differences in ACEs prevalence and differences in provider-diagnosed chronic emotional and developmental conditions, health characteristics, reported child behaviors, and health services received as a function of having multiple ACEs. AI/AN children were more likely to have experienced 2+ ACEs (40.3% versus 21%), 3+ ACEs (26.8% versus 11.5%), 4+ ACEs (16.8% versus 6.2%), and 5+ ACEs (9.9% versus 3.3%) compared to NHW children. Prevalence rates for depression, anxiety, and ADHD were higher among AI/AN children with 3+ ACEs (14.4%, 7.7%, and 12.5%) compared to AI/ANs with fewer than 2 ACEs (0.4%, 1.8%, and 5.5%). School problems, grade failures, and need for medication and counseling were 2-3 times higher among AI/ANs with 3+ ACEs versus the same comparison group. Adjusted odds ratio for emotional, developmental, and behavioral difficulties among AI/AN children with 2+ ACEs was 10.3 (95% CI = 3.6-29.3). Race-based differences were largely accounted for by social and economic-related factors.

Moon, H., Lee, Y. S., Roh, S., & Burnette, C. E. (2018). Disparities in health, health care access, and life experience between American Indian and White adults in South Dakota. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities, 3 (2), 301-308. doi:10.1007/s40615-015-0146-3.

Article Summary

The objective of this study is to investigate the factors associated with depressive symptoms and chronic illnesses in American Indians compared with White adults born in the post-World War II period, 1946 to 1964, and living in South Dakota.

Design: A cross-sectional design of American Indian and White adults aged 50 and older in South Dakota (Brookings, Vermillion, Sioux Falls, and all other areas of South Dakota) between January 2013 and May 2013 was used. American Indian and White adults (born between 1946 and 1964; N = 349). Data included sociodemographic factors and measures of chronic physical health condition, health care access, adverse childhood experiences, body mass index (BMI), Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, Technology Acceptance Model, and Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support and Depressive Symptoms.

Results: American Indian adults reported more chronic diseases and conditions, a lower self-perceived physical health, were more likely to be overweight or obese, had more adverse childhood experience (ACE), and reported a lower level of alcohol intake compared to White adults. BMI was significantly associated with an increased number of chronic conditions for both groups, and American Indians' better perception of their physical health was significantly associated with lower total number of chronic conditions. Self-perceived mental health, a better level of access to health care, and a higher degree of social support were significantly inversely associated with the number of depressive symptoms for American Indian adults, while a greater number of ACEs was significantly associated with an increased number of depressive symptoms for this group.

Conclusion: The current study not only support previous studies but also contributes to understanding the disparities in and risk factors potentially impacting American Indians' physical and mental health. Our findings highlight the need to investigate the American Indians' perceptions and knowledge about health care accessibility including availability as well as perceived barriers including social sensitivity and trust. Health professionals might need to pay attention to BMI, ACE, and social relationship among American Indian adults to improve physical and mental health.

Warne, D., Dulacki, K., Spurlock, M., Meath, T., Davis, M. M., Wright, B., & McConnell, K. J. (2017). Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) among American Indians in South Dakota and associations with mental health conditions, alcohol use, and smoking. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 28(4), 1159-1577. doi:10.1353/hpu.2017.0133

Article Summary

Objectives: To assess the prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and their association with behavioral health in American Indian (AI) and non-AI populations in South Dakota.

Methods: We included the validated ACE questionnaire in a statewide health survey of 16,001 households. We examined the prevalence of ACEs and behavioral health conditions in AI and non-AI populations and associations between ACEs and behavioral health.

Results: Compared with non-AIs, AIs displayed higher prevalence of ACEs including abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and had a higher total number of ACEs. For AIs and non-AIs, having six or more ACEs significantly increased the odds for depression, anxiety, PTSD, severe alcohol misuse, and smoking compared with individuals with no ACEs.

Conclusions: American Indians in South Dakota experience more ACEs, which may contribute to poor behavioral health. Preventing and mitigating the effects of ACEs may have a significant impact on health disparities in AI populations.

Evidence suggests that adverse childhood experiences and social conditions in AI communities contribute to poor health outcomes for AIs.

Moon, H., Lee, Y. S., Roh, S., & Burnette, C. E. (2018). Factors associated with American Indian mental health service use in comparison with White older adults. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities, 5(4), 847-859. doi:10.1007/s40615-017-0430-5

Article Summary

Objective : Our objective was to identify the factors that impact mental health service use among American Indian (AI) older adults living in South Dakota compared to their White counterparts.

Design and Methods : Using a cross-sectional design with 735 participants (n = 502 Whites, n = 233 AIs), we used ordinal regressions to analyze the extent to which predisposing, need, and enabling/hindering factors predicted the level of mental health service utilization.

Results : White older adults used more mental health services as compared with AI older adults. For both groups, more adverse childhood experiences along with prior negative experience with mental health service use were significantly related to an increased level of mental health service use. Compared to their White counterparts, AI older adults who reported a higher level of depressive symptoms, better self-perceived physical health, and a more positive attitude toward mental health services tended to use more mental health services.

Conclusions : To reduce mental health disparities among AI older adults, community, local government, and academic partners should pay attention to how to encourage the use of mental health services to meet the unique needs of AI older adults.

Roh, S., Burnette, C. E., Lee, K. H., Lee, Y. S., Easton, S. D., & Lawler, M. J. (2015). Risk and protective factors for depressive symptoms among American Indian older adults: Adverse childhood experiences and social support. Aging Ment Health, 19(4), 371-380. doi:10.1080/13607863.2014.938603.

Article Summary

Objectives: Despite efforts to promote health equity, many American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) populations, including older adults, experience elevated levels of depression. Although adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and social support are well-documented risk and protective factors for depression in the general population, little is known about AI/AN populations, especially older adults. The purpose of this study was to examine factors related to depression among a sample of AI older adults in the Midwest.

Method: Data were collected using a self-administered survey completed by 233 AIs over the age of 50. The survey included standardized measures such as the Geriatric Depression Scale-Short Form, ACE Questionnaire, and the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Hierarchical multivariate regression analyses were conducted to evaluate the main hypotheses of the study.

Results: Two dimensions of ACE (i.e., childhood neglect, household dysfunction) were positively associated with depressive symptoms; social support was negatively associated with depressive symptoms. Perceived health and living alone were also significant predictors.

Conclusion: ACE may play a significant role in depression among AI/AN across the life course and into old age. Social support offers a promising mechanism to bolster resilience among older adults.

Brockie, T. N., Elm, J. H. L., & Walls, M. L. (2018). Examining protective and buffering associations between sociocultural factors and adverse childhood experiences among American Indians with type 2 diabetes: a quantitative, community-based participatory research approach.BMJ Open, 8(e022265). doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022265 .

Article Summary

Objectives: The purpose of this study was to determine the frequency of select adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) among a sample of American Indian (AI) adults living with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and the associations between ACEs and self-rated physical and mental health. We also examined associations between sociocultural factors and health, including possible buffering processes.

Design: Survey data for this observational study were collected using computer-assisted survey interviewing techniques between 2013 and 2015.

Setting: Participants were randomly selected from AI tribal clinic facilities on five reservations in the upper Midwestern USA.

Participants: Inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of T2D, age 18 years or older and self-identified as AI. The sample includes n=192 adults (55.7% female; mean age=46.3 years).

Primary measures: We assessed nine ACEs related to household dysfunction and child maltreatment. Independent variables included social support, diabetes support and two cultural factors: spiritual activities and connectedness. Primary outcomes were self-rated physical and mental health.

Results: An average of 3.05 ACEs was reported by participants and 81.9% (n=149) said they had experienced at least one ACE. Controlling for gender, age and income, ACEs were negatively associated with self-rated physical and mental health (p<0.05). Connectedness and social support were positively and significantly associated with physical and mental health. Involvement in spiritual activities was positively associated with mental health and diabetes-specific support was positively associated with physical health. Social support and diabetes-specific social support moderated associations between ACEs and physical health.

Conclusions: This research demonstrates inverse associations between ACEs and well-being of adult AI patients with diabetes. The findings further demonstrate the promise of social and cultural integration as a critical component of wellness, a point of relevance for all cultures. Health professionals can use findings from this study to augment their assessment of patients and guide them to health-promoting social support services and resources for cultural involvement.

De Ravello, L., Abeita, J., & Brown, P. (2008). Breaking the cycle/mending the hoop: Adverse childhood experiences among incarcerated American Indian/Alaska Native women in New Mexico. Health Care Women Intl, 29(3), 300-315. doi:1080/07399330701738366.

Article Summary

Incarcerated American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) women have multiple physical, social, and emotional concerns, many of which may stem from adverse childhood experiences (ACE). We interviewed 36 AI/AN women incarcerated in the New Mexico prison system to determine the relationship between ACE and adult outcomes. ACE assessment included physical neglect, dysfunctional family (e.g., household members who abused substances, were mentally ill or suicidal, or who were incarcerated), violence witnessed in the home, physical abuse, and sexual abuse. The most prevalent ACE was dysfunctional family (75%), followed by witnessing violence (72%), sexual abuse (53%), physical abuse (42%), and physical neglect (22%). ACE scores were positively associated with arrests for violent offenses, lifetime suicide attempt(s), and intimate partner violence.

Adolescent Violence Perpetration: Associations with Multiple Types of Adverse Childhood Experiences

Duke, N. N., Pettingell, S.L., McMorris, B.J., & Borowsky, I.W. (2010). Adolescent violence perpetration: Associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics, 125(4), e778-e786.

Article Summary

Objective: Adverse childhood experiences are associated with signi?cant functional impairment and life lost in adolescence and adulthood. This study identi?ed relationships between multiple types of adverse events and distinct categories of adolescent violence perpetration.

Methods: Data are from136,549 students in the 6th, 9th, and 12th grades who responded to the 2007 Minnesota Student Survey, an anonymous, self-report survey examining youth health behaviors and perceptions, characteristics of primary socializing domains, and youth engagement. (Note: AI/AN = 1975 or 1.5%). Linear and logistic regression models were used to determine if 6 types of adverse experiences including physical abuse, sexual abuse by family and/or other persons, witnessing abuse, and household dysfunction caused by family alcohol and/or drug use were signi?cantly associated with risk of adolescent violence perpetration after adjustment for demographic covariates. An adverse-events score was entered into regression models to test for a dose-response relationship between the event score and violence outcomes. All analyses were strati?ed according to gender.

Results: More than 1 in 4 youth (28.9%) reported at least 1 adverse childhood experience. The most commonly reported adverse experience was alcohol abuse by a household family member that caused problems. Each type of adverse childhood experience was signi?cantly associated with adolescent interpersonal violence perpetration (delinquency, bullying, physical ?ghting, dating violence, weapon-carrying on school property) and self-directed violence (self-mutilation behavior, suicidal ideation, mutilation behavior and suicide attempt). For each additional type of adverse event reported by youth, the risk of violence perpetration increased 35% to 144%.

Conclusions: Multiple types of adverse childhood experiences should be considered as risk factors for a spectrum of violence-related outcomes during adolescence. Providers and advocates should be aware of the interrelatedness and cumulative impact of adverse-event types. Study ?ndings support broadening the current discourse on types of adverse events when considering pathways from child maltreatment to adolescent perpetration of delinquent and violent outcomes.

Risk Factors for Physical Assault and Rape among Six Native American Tribes

Yuan, N. P., Koss, M.P., Polacca, M., & Goldman, D. (2006). Risk factors for physical assault and rape among six Native American tribes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21(2), 1566-1590, doi. 10.1177/0886260506294239.

Article Summary

Prevalence and correlates of adult physical assault and rape in six Native American tribes are presented (N = 1,368). Among women, 45% reported being physically assaulted and 14% were raped since age 18 years. For men, figures were 36% and 2%, respectively. Demographic characteristics, adverse childhood experiences, adulthood alcohol dependence, and cultural and regional variables were assessed. Using logistic regression, predictors of physical assault among women were marital status, an alcoholic parent, childhood maltreatment, and lifetime alcohol dependence. Among men, only childhood maltreatment and lifetime alcohol dependence predicted being physically assaulted. Tribal differences existed in rates of physical assault (both sexes) and rape (women only). The results underscore the problem of violence victimization among Native Americans and point to certain environmental features that increase risk of adulthood physical and sexual assault.

This section includes examples of how Tribes and organizations are integrating protective factors and ACE prevention strategies to impact the health and well-being of AI/AN people. Resources are placed in one of 3 categories:

The Alaska Resilience Initiative's shared goal is to end maltreatment, intergenerational and systemic trauma through healing and strategic advocacy. It serves as an umbrella role for adverse childhood experiences, trauma and resilience work in Alaska--supporting and bringing together those doing the work. The Alaska Resilience Initiative is a network of nonprofit, tribal and state government organizations, schools, businesses and community coalitions working to solve complex social problems and promote a healthy, just and resilient Alaska. It is a repository of tools and resources for those in Alaska working on Adverse Childhood Experiences.

Confronting Adverse Childhood Experiences to Improve Rural Kids' Lifelong Health

The Rural Health Information Hub has links to resources and information about rural communities by state. In this article, readers learn about ACEs in rural America, and ACE learning collaboratives. One way these communities have addressed ACEs is through trauma-informed school programs, or Compassionate Schools. This article explains more about ACEs and trauma-informed school programs.

Family Spirit is an evidence-based AI/AN teen mother tribal home visiting program designed to address behavioral health disparities among AI and evaluated by using measures of intervention fidelity and early childhood emotional/behavioral development. This program targets maternal health, child development, school readiness, and positive parenting practices.

ACE Targeted Resources for Tribal Child Welfare, February 2018

This website provides accessible information related to ACEs from theCenters for Disease Control, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. There is also an opportunity to connect to a free network with various community groups, including one with a shared goal of reducing ACEs in Native communities.

Addressing Trauma in American Indian and Alaska Native Youth

Amanda Lechner, Michael Cavanaugh, and Crystal Blair

Mathematica Policy Research conducted an environmental scan of practices and programs for addressing trauma and related behavioral health needs in AI/AN youth for the U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. This 62-page report provides information on trauma-informed care and trauma-specific interventions; interventions focused on suicide prevention and substance use disorders; and parenting interventions for youth and their guardians. It describes frameworks and common elements of effective interventions and discusses policy implications.

Association of American Indian Physicians

This site discusses the impact of ACE on American Indian/Alaska Native communities. It offers supporting information for strategies to buffer or prevent these episodes and provides links to additional resources.

This is a governmental report with policy recommendations based upon hearings and listening sessions nationwide to learn from key practitioners, advocates, academicians, policy makers, and the public about the issue of American Indian and Alaska Native children exposed to violence in the United States in and outside of Indian Country. Included in the report is information on promising and evidence-based practices that could benefit children and their communities.

The Indian Country Child Trauma Center (ICCTC) developed cultural adaptations of two evidence-based practices, Trauma Focused Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Problematic Sexual Behavior Cognitive Behavior Therapy (PSB-CBT), to mitigate the impact of trauma and ACEs with AI/AN youth. A brief overview of ACEs within the AI/AN context is provided, along with a description of these culturally enhanced treatments and implications for future research, practice and policy.

How Native American children benefit from trauma-informed schools.

This electronic article describes Montana's Wraparound program, a trauma-sensitive practice to address children's mental health, behavioral, and academic issues. Trauma-sensitive schools create safety-physical, social, and emotional-for students who may have experienced trauma. The goal is to create schools where adults-from the principal to the lunchroom personnel-consistently respond to children with empathy and compassion.

Wisconsin aims to be first trauma-informed state; seven state agencies lead the way

This article describes the work of Wisconsin in the implementation of trauma-informed practices based on ACEs science.

New Mexico Youth Risk and Resiliency Survey

The NM Youth Risk and Resiliency Survey (YRRS) is a tool to assess the health risk behaviors and resiliency (protective) factors of New Mexico high school and middle school students. The YRRS is part of the national CDC Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS). The survey results have widespread benefits for New Mexico at the state, county, and school district levels. The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, Public Health and Human Services Division has partnered with Cherokee Central Schools for 4 years to conduct this survey with middle and high school students (2016 & 2018). While not specifically ACEs-organized, it assesses similar conditions while also incorporation a set of resiliency questions. It is also possible to compare outcomes with student data from New Mexico.

ACE Resources Specific to American Indians/Alaska Natives

Resources in this section include websites, power point presentations, videos, fact sheets, reports, surveys, training opportunities and technical assistance specific and applicable to ACEs and AI/AN populations.

Health disparities in North Dakota are pronounced; the average age at death is 20 years younger than Whites. In this poster, researchers report on the prevalence of nine adverse childhood and family experiences (ACFE) among American Indian children in North Dakota and explore disparities in exposure to ACFEs among American Indian children and White children in the state.

California Tribal Epidemiology Center

The California Tribal Epidemiology Center modified the ACE survey in order to place within our Adult (18+) California Tribal Behavioral Risk Factor Survey (BRFS). The goal of this survey was to identify and understand priority health-related behaviors of American Indian/Alaska Natives in California. The questions created by the California Tribal Epidemiology center are attached in the appendices.

Childtrends presents information to aid understanding of the structural, historic, and systemic contexts that relate to limited ACEs data for American Indians and Alaska Natives and explains the disproportionate exposure to ACEs among this population. Three factors are important to consider in support of more equitable outcomes: AI/AN population characteristics, historical trauma and resilience, and tribal sovereignty.

Facts on Violence Against American Indian/Alaska Native Women

Futures Without Violence has compiled statistics for American Indian and Alaska Native women and violence, including: domestic violence/intimate partner violence/physical violence; sexual assault; stalking; health connections/risk factors; children and youth; victim perspective, historical trauma, jurisdictional/sovereignty problems; lack of resources/social isolation on reservations; and emerging trends/interventions.

Indian Health Service (IHS) offers information about ACEs. IHS is also a contact for additional support.

Minnesota Department of Health

Minnesota Department of Health prepared a comprehensive report on ACEs and Minnesotans based on 2011 data. The report contains a brief introduction about ACE as well as explanations for connections of ACE to brain development and stress. Comparisons are made between Minnesotans and national data for all ages with detailed charts and graphs. Conclusions include next steps and policy recommendations. This report exemplifies how Tribes and other government entities can prepare a locally relevant research document.

Tribal Epidemiology Centers (TECs)

TEC are Indian Health Service, division-funded organizations which serve American Indian/Alaska Native Tribal and urban communities by managing public health information systems, investigating diseases of concern, managing disease prevention and control programs, responding to public health emergencies, and coordinating these activities with other public health authorities.

The NEAR acronym stands for Neuroscience, Epigenetics, ACEs, and Resilience. This website and toolkit provide information for those professionals who make home visits to families but worry about causing harm. The NEAR@Home toolkit addresses these concerns and provides strategies for engaging parents in discussing and using the ACEs questionnaire in a safe, respectful, and effective way for both home visitor and family.

This page offers access to a webinar presented by Dr. Bigfoot about the Kaiser Permanente Study and adverse childhood experiences with a focus on American Indian and Alaska Native children. The viewer may need to download Adobe Connect (instructions are provided).

Examining the Theory of Historical Trauma among Native Americans

The theory of historical trauma was developed to explain the current problems facing many Native Americans. This theory purports that some Native Americans are experiencing historical loss symptoms (e.g., depression, substance dependence, diabetes, dysfunctional parenting, unemployment) as a result of the cross-generational transmission of trauma from historical losses (e.g., loss of population, land, and culture). However, there has been skepticism by mental health professionals about the validity of this concept. The purpose of this article is to systematically examine the theoretical underpinnings of historical trauma among Native Americans. The author seeks to add clarity to this theory to assist professional counselors in understanding how traumas that occurred decades ago continue to impact Native American clients today.

The immediate and long-term effects of ACES

This site describes the outcomes of ACE trainings in Montana, including outcomes that have direct Tribal impact. It also includes a summary of the connection between ACEs, historical trauma, and resilience.

John Hopkins Center for American Indian Health

The Center for American Indian Health conducts research and trainings on a variety of programs that impact the health and wellbeing of Native communities, including Family Spirit Home Visiting Program, an evidence-based, culturally tailored home-visiting program to promote optimal health and wellbeing for parents and children.

Native American tribal communities provide hope for overcoming historical trauma

Pine Ridge Indian Reservation is the eighth largest reservation in the country and is struggling with high suicide rates, unemployment, poverty, and low life expectancies. This article describes the history and impact of historical trauma on Pine Ridge and efforts to address and overcome it, including a description of the historical trauma intervention model.

The Nuts and Bolts of Successfully Working with Tribes and Tribal Entities

The Washington State Department of Health has compiled information to aid individuals interested in working with Tribes and Tribal entities. Included on the site is information about Native epistemology and information on replicating the recommendations in other states/sites.

This PowerPoint presentation describes the use of a community-based symposium as an intervention to increase awareness of the prevalence and health effects of violence, abuse, and neglect across the lifespan; to highlight community strengths, and to enhance quality of patient care and improve patient outcomes. Slides include ACE data and statistics for Montana in 2010.

Trauma may be woven into DNA of Native Americans - Intergenerational trauma is real

This 2017 article explains the science of epigenetics in lay terms and discusses the implications of inherited epigenetic changes based upon historical trauma using the work of Teresa Brockie, PhD, Research Nurse Specialist at the National Institute of Health.

Understanding Impacts and Implementing Strategies

This PowerPoint presentation explains ACEs and the impact among Native Americans. Slides include tables, graphs and charts and includes information on brain development and adversity/stress. This is information specific to children and adults, including techniques for interventions .

This section includes ACE resources more general in context (not AI/AN specific) that can add to foundational and practical knowledge about ACEs. Resources are in alphabetical order by title.

This a short video about adverse childhood experiences. If offers a concise history of the development of ACEs and how the survey can be used as a prevention mechanism. In the words of the researcher, "If it can be predicted, it can be prevented."

Resources Center promotes education and provides a structure for building initiatives. The site includes links to instruments used by primary care providers and surveys in Spanish, and groups forming around the world to promote efforts to reduce ACE.

ACEs Too High is a news site that reports on research about adverse childhood experiences, including developments in epidemiology, neurobiology, and the biomedical and epigenetic consequences of toxic stress. It also covers how people, organizations, agencies and communities are implementing practices based on the research. This includes developments in education, juvenile justice, criminal justice, public health, medicine, mental health, social services, and cities, counties and states.

Exploring the Rural Context for Adverse Childhood Experiences

A policy brief and recommendations prepared by the National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention - Adverse Childhood Experiences

Mobilizing Action for Resilient Communities (MARC)

Trauma in Children and Adolescents: An Overview (designed for medical providers)

Rebecca Ezechukwu, University of New Mexico

This site describes the ACE study as well as trauma/grief, traumatic stress, post-traumatic stress and how children and youth in a variety of situations (refugee, military family, American Indian) react in stressful environments. It includes how to talk to youth in a beneficial way and how to offer help.

This page has a series of links about ACEs training; infographics that visually represent ACE data, a tool that provides insight into how ACEs can be prevented and how to minimize effects and case studies that provide detailed descriptions of how selected states (Alaska, Oklahoma, Washington, and Wisconsin) have valued and used ACE data to inform their child abuse and neglect prevention efforts. Other links offer information on preventing child abuse and neglect.

Resources in this section include available instruments used in the AI/AN-specific ACE research. When planning local needs assessments and data collection, it is important to use instruments that have been tested within AI/AN populations.

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-IA)

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (28 items), (For Purchase)

Geriatric Depression Scale-Short Form

Historical Loss-Associated Symptoms

Separate document.

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support

Perceived Discrimination Scale

Semi-structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA)