Doctrine of Discovery and its Impact on American Indian and Alaska Native Health Care

In 1492, Christopher Columbus set out, on behalf of the Spanish government, to find a nautical eastern passage to Asia. Much to the surprise of Spain and all of the European powers, Columbus instead found a land mass that had been inhabited since time immemorial. This was one of the first recorded contacts between the European and Tribal nations. Under the diplomatic norms of the 15th century, Columbus and Spain could have sought to establish diplomatic ties between the nations, which might have led to trade opportunities between the Tribes and Europe. However, the European powers had other ideas. Avoiding any pretense of diplomacy, the Catholic Church sought to legally justify settlement of the land mass, which they would later call “America.”

In 1492, Christopher Columbus set out, on behalf of the Spanish government, to find a nautical eastern passage to Asia. Much to the surprise of Spain and all of the European powers, Columbus instead found a land mass that had been inhabited since time immemorial. This was one of the first recorded contacts between the European and Tribal nations. Under the diplomatic norms of the 15th century, Columbus and Spain could have sought to establish diplomatic ties between the nations, which might have led to trade opportunities between the Tribes and Europe. However, the European powers had other ideas. Avoiding any pretense of diplomacy, the Catholic Church sought to legally justify settlement of the land mass, which they would later call “America.”

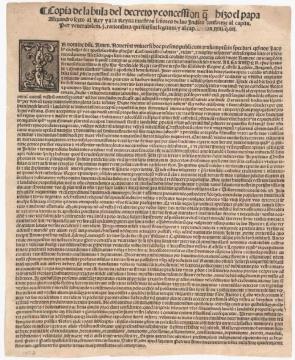

On May 4, 1493, Pope Alexander VI issued a Papal Bull called “Inter Caetera,” which provided justification for Christian nations to encroach upon the sovereignty of non-Christian nations by declaring, “that barbarous nations be overthrown and brought to the faith itself.” This document provided a “legal” justification for the colonization of the Americas by declaring that the sovereignty of Christian nations supersedes that of non-Christian nations. It also presented a theme that would permeate the relationship between Tribal nations and the European powers, as well as their successor sovereign, the United States of America. The document provided justification for the belief that being non-Christian (or “non-civilized”) made you less than human.

This philosophy persisted during the founding of the United States of America. In 1776, Thomas Jefferson wrote in the Declaration of Independence of the “merciless Indian savages.” Furthermore, despite the United States Constitution specifically recognizing the sovereignty of Tribal nations, the United States Supreme Court incorporated the Doctrine of Discovery into U.S. law in 1824’s Johnson v. Mc’Intosh when they stated that “discovery gave title to the government by whose subjects or by whose authority it was made against all other European governments, which title might be consummated by possession … [t]he history of America from its discovery to the present day proves, we think, the universal recognition of these principles. 1

The declaration that “barbarous nations be … brought to the faith itself” was also foundational in understanding the approach to education that the European countries and the U.S. would take with native people. Even before the official establishment of federal Indian boarding schools in the late 19th century, there were schools designed to “Christianize” native people. A notable example was Moor’s Charity School in Lebanon, Connecticut, which was established by Rev. Eleazar Wheelock. Wheelock would use the “success” of Moor’s Charity School to raise money for the establishment of Dartmouth College in 1769. Dartmouth’s charter included that it was founded, in part, “for the education and instruction of youth of the Indian Tribes in this land in reading, writing, and all parts of learning which shall appear necessary and expedient for civilizing and Christianizing children of pagans[.]” Many of these early schools were founded by Christian groups, often missionaries, and often with the full support of European powers, and later the U.S. government. In 1819, Congress passed the Civilization Fund Act, which provided funding to these groups to establish and operate boarding schools.

The declaration that “barbarous nations be … brought to the faith itself” was also foundational in understanding the approach to education that the European countries and the U.S. would take with native people. Even before the official establishment of federal Indian boarding schools in the late 19th century, there were schools designed to “Christianize” native people. A notable example was Moor’s Charity School in Lebanon, Connecticut, which was established by Rev. Eleazar Wheelock. Wheelock would use the “success” of Moor’s Charity School to raise money for the establishment of Dartmouth College in 1769. Dartmouth’s charter included that it was founded, in part, “for the education and instruction of youth of the Indian Tribes in this land in reading, writing, and all parts of learning which shall appear necessary and expedient for civilizing and Christianizing children of pagans[.]” Many of these early schools were founded by Christian groups, often missionaries, and often with the full support of European powers, and later the U.S. government. In 1819, Congress passed the Civilization Fund Act, which provided funding to these groups to establish and operate boarding schools.

In 1871, the U.S. ceased treaty making with Tribes and began moving towards a policy of complete eradication of Tribal nations. One of the primary means for achieving this policy goal involved the creation of boarding schools that would “civilize” native children and indoctrinate them into mainstream American society. It was to be the final phase of the call “that barbarous nations be overthrown and brought to the faith itself” that had been made almost 400 years prior and the end goal of the Doctrine of Discovery. Upon the founding of the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, General Richard Henry Pratt declared his mission was to “kill the Indian and save the man.”

The establishment of Carlisle Indian school marked a turning point. No longer was the U.S. government (and the states) content to issue charters and funding to private individuals like Wheelock, it was itself moving into the business of “civilizing” native people. The formal establishment of the boarding schools represented a more aggressive approach to fulfilling the call of “Inter Caetera.” The Carlisle Indian School was one of many boarding schools founded for this purpose, and was operated from 1879 to 1918. After Carlisle’s closure, boarding schools continued to operate throughout the 20th century. In those years, countless native children were involuntarily removed from their homes and forced into a strange land, hundreds of miles from homelands. Many of them never returned. The decision to send children so far from home was intentional. The boarding schools were to remove the child far from their home, customs, and family ties to force them to become “civilized.”

The boarding school experiment was a failure in countless ways. Tribal nations are still here, and we persist despite repeated attempts at termination. It also never met General Pratt’s goal of “saving the man.” In fact, the boarding schools caused incalculable harm to native people. Generations of children were taken from their homes with many of them dying and being buried in mass graves. Those that survived the experience were left with trauma from the harsh conditions of the boarding schools. Entire generations of many Tribes were lost, to both death and despondency from the trauma caused by the experience.

Native people have had to reckon with the historical trauma caused by the boarding schools and their predecessors. The Doctrine of Discovery is directly to blame for the boarding school experience. The call “that barbarous nations be overthrown and brought to the faith itself” fed an insidious ideology that prioritized “civilizing” native children over providing for their well-being. It provided justification for the disruption of native communities, in pursuit of the nebulous goal of “civilization.” It provided justification for the subjugation of Tribal sovereignty that would even make such an undertaking possible. Understanding the boarding school experience requires understanding the ideology that led to its existence. The Doctrine of Discovery has caused untold amounts of damage to native communities and our people continue to reckon with its fallout.

- Johnson & Graham's Lessee v. McIntosh, 21 U.S. 543, 573-574 (1823)

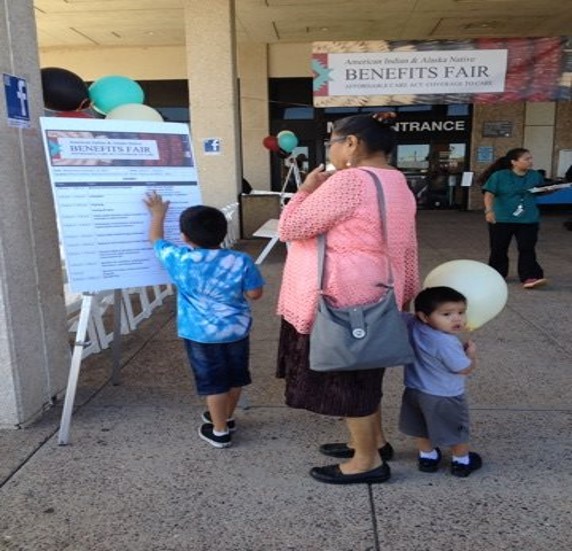

It comes as no surprise over the past two years, COVID-19 has greatly impacted access to health care in Tribal communities. The pandemic highlights a severe need of enrollment into health insurance for many Tribal communities and American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) populations. It showcases the need for additional resources in Indian Country to provide effective and accurate outreach and education on health care insurance.

It comes as no surprise over the past two years, COVID-19 has greatly impacted access to health care in Tribal communities. The pandemic highlights a severe need of enrollment into health insurance for many Tribal communities and American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) populations. It showcases the need for additional resources in Indian Country to provide effective and accurate outreach and education on health care insurance.