The Special Diabetes Program for Indians (SDPI) serves 780,000 American Indians and Alaska Natives across 302 programs in 35 states.1 SDPI focuses on community-directed approaches to treat and prevent Type 2 diabetes in Tribal communities that are culturally informed. American Indians and Alaska Natives suffer disproportionately from Type 2 diabetes, but thanks to the success of SDPI, that statistic is improving.

SDPI expires on September 30, 2023 and Congress is currently considering the reauthorization. The Congressional Diabetes Caucus led the effort in circulating a bipartisan sign-on letter requesting support to reauthorize SDP and SDPI. With the help of NIHB and other partners, the letters received 60 Senate signers and 240 House signers. However, these letters do not reauthorize the program.

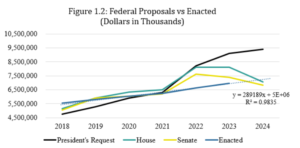

SDPI has not seen a funding increase in 20 years. Legislation was introduced in the House (H.R. 3561) and Senate (S. 1855) that would reauthorize the SDPI program at $170 million in annual funding for two years. Both of these bills have passed out of their respective committees but are waiting for a floor vote to be scheduled in their respective chambers. SDPI is the most effective effort to combat diabetes and its complication, therefore, reauthorization must be a top priority.

Even though SDPI is widely bipartisan, with federal funding deadlines approaching and a closely divided Congress, SDPI renewal is not guaranteed.

We need your help! Please contact your member of Congress and let them know that SDPI must be renewed by the end of September! You can find SDPI fact sheets and information here.

More background on SDPI below:

Congress established the Special Diabetes Program for Indians (SDPI) in 1997 as a mandatory funding program as part of the Balanced Budget Act to address the growing epidemic of diabetes in American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) communities. The Special Diabetes Program for Type 1 Diabetes (SDP) was established at the same time to address the opportunities in type 1 diabetes research. Together, these programs have become the nation’s most strategic, comprehensive, and effective efforts to combat diabetes and its complications.

At a rate approximately 2 times the national average, AI/ANs have the highest prevalence of diabetes. In some AI/AN communities, over 50% of adults have been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and AI/ANs are 1.8 times more likely to die from diabetes.

SDPI has become the nation’s most effective federal initiative to combat diabetes. Thanks to SDPI, for the first time, from 2013 to 2017 diabetes incidence in AI/ANs decreased each year. AI/ANs are the only racial/ethnic group that have seen a decrease in prevalence. Fewer cases have coincided with a decrease in diabetes related mortality by 37 percent between 1999 and 2017. SDPI has also resulted in significant savings from Medicare due to reduction in End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD). Between 1996 and 2013, incidence rates of ESRD in AI/AN individuals with diabetes declined by 54 percent. This reduction alone is estimated to have already saved $520 million between 2006-2015.2 Hospitalizations for uncontrolled diabetes among AI/AN people has also dropped by 84 percent, which significantly lowers health care costs.

This success is due to the nature of this grant program which is administered at the federal level but is implemented locally. This design has allowed Tribal communities to design and implement diabetes interventions that address locally identified community priorities. Tribal leaders have identified community adaptability to be a strong element of SDPI’s success. They have shared that the ability of the community to make local level decisions, choose best practices, and adapt the program to be culturally appropriate has been vital to its success. Communities with SDPI-funded programs have seen substantial growth in diabetes prevention resources, including more than doubling the number of on-site nutrition services, and physical activity and weight management specialists for adults, and an exponential increase of sites with physical activity services for youth.

Programs are able to address the most urgent needs in their communities, and this has led to incredible results both locally and nationally. Programs have reported improvements in A1Cs, blood pressure, diabetes-related eye disease outcomes, and foot health of their patients. Because programs are locally led, staff are often able to incorporate both traditional practices and evidence-based prevention. This combined approach has led to significant community buy-in. Kevin Fortuin, the SDPI Program Manager for Tohono O’odham Nation shared “O’odham people have always been traditional runners. The connection between traditional foods, activity, and exercise is tied not only to health, wellness, diabetes prevention, and management, but also in terms of who the O’odham people are. It’s part of the O’odham culture.”

SDPI has been so successful that it has been recognized as one of the most successful public health interventions in our nation’s history, after childhood vaccination. SDPI models have been applied to other populations as well. One state Medicaid agency actually contracts with SDPI programs to treat the non-native population in the state because the methods are so effective.

Unfortunately, SDPI has faced significant uncertainty with stagnant funding and short-term reauthorizations. A 2020 NIHB survey found that 43 percent of SDPI programs faced challenges related to cutbacks in services due to funding uncertainty, and 39 percent of programs faced potential delays in purchasing medical equipment.[3] “The uncertainty of funding has resulted in the need to prioritize personnel expenses over other program-related expenses… As such, the participation of SDPI staff in events such as the annual Village Health Fairs was placed in potential jeopardy,” one respondent shared. Another respondent stated their program faced challenges, including, “not being able to hire staff for program activities in a timely manner [and] not being able to maintain staff due to uncertainties.”