The National Indian Health Board (NIHB) is committed to advocating for the health and well-being of Indigenous communities. One of our key initiatives focuses on addressing adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which are traumatic events occurring during childhood. Research indicates that Indigenous children experience higher ACEs and collective trauma, which needs to be addressed through Indigenous frameworks. We are working to reduce the impact of ACEs within Indigenous communities by raising awareness, providing resources, and advocating for policy changes. Indigenous frameworks offer a holistic approach to healing that focuses on the interconnectedness of all things and the importance of spiritual connection for healing the heart, body, mind, and spirit.

ACEs are stressful and traumatic events experienced during childhood, up to age 17, such as experiencing abuse or neglect or witnessing violence in the home. ACEs can have negative effects on health, opportunities, and overall well–being.1

ACEs have been associated with poor physical, mental, and behavioral health outcomes. CDC reports that ACEs can elevate the risk of injuries, sexually transmitted infections, maternal and child health issues, and involvement in sex trafficking.1 ACEs can also be linked to other chronic diseases and leading causes of death, including cancer, diabetes, heart disease, and suicide.1

For these reasons, addressing ACEs is important to creating healthier individuals and building stronger Indigenous communities.

NIHB created a 2024 special report on ACEs that you can read here.

On this page and throughout our tabs, we use the term Indigenous Peoples, American Indian and Alaska Native, Tribal Nations, and Native American interchangeably as cited by literature, public health professionals and Indigenous people. We recognize there are distinct differences, beliefs, and traditions across Indian Country. We honor those differences and what we share here may not be representative of all Indigenous Peoples within the United States of America.

A study completed by Giano et al., (2021) used Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) data across 34 states between 2009 to 2017.3 It is one of the largest studies of ACES for AI/AN communities to date. Their key findings revealed:

Another study by Kenney & Singh, (2016) examined ACEs among AI/AN children (aged 0-17 years) using parental responses from the 2011-2012 National Survey of Children’s Health.4 Their findings revealed that:

Specifically, AI/AN children were at least twice as likely as NHW children4 to have the following:

Additionally, AI/AN children were 1.5–1.7 times4 more likely to have:

ACEs are usually measured by individual adversity, but adverse experiences can also be collective. The ongoing effects of colonization, history of wars, displacement, and systemic oppression continue to negatively impact the health of Indigenous individuals, families, and communities.5 This historical trauma, which includes forced assimilation and cultural suppression through mechanisms like residential boarding schools, has intergenerational trauma and cumulative effects that still affect the health of Indigenous Peoples today.5

It is important to note that the studies by Giano et al. (2021) and Kenney & Singh (2016) did not incorporate a cultural context or utilize an Indigenous framework. The constructs of ACEs are limited and fail to consider the historical trauma and unique experiences of Indigenous peoples. The ongoing and historical health inequities and deficiencies are a result of U.S. government policies and practices related to healthcare programs and services provided to Tribal Nations. These issues arise from social, political, economic disadvantages that hinder Tribal Nations from achieving and maintaining good health and accessing resources that support optimal health outcomes. Addressing and improving health outcomes, particularly positive childhood experiences, requires decolonization and reconciliation. However, NIHB is actively collaborating with federal agencies, including the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, to address and improve health inequities within Indian Country through various cooperative agreements.

Decolonization refers to the right and ability of Indigenous peoples to practice self–determination over their land, cultures, political, and economic systems.6 This means returning control of Indigenous health, healthcare systems, healthcare delivery, and wellness to Indigenous communities and recognizing Indigenous knowledge systems as equal to Western ways.

Reconciliation, on the other hand, means to restores friendships or harmony.7 From an Indigenous perspective, it means addressing past wrong doings and building a better future by improving the relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. This involves acknowledging historical injustices, making amends, and working towards mutual understanding and respect. Ultimately, it means respecting Indigenous Sovereignty and funding Tribal Nations to the fullest capacity and enabling them to create Indigenous frameworks that best serve their needs.

For additional studies, please refer to this factsheet8 from National Native Children’s Trauma Center.

“We tell our children they are Indigenous and that means they need to be resilient, as if it is a great strength. But the painful truth is that our children should not have to endure this burden. They should not have to bear the consequences of colonialism, oppression, lack of resources, and continuous trauma. They weight of historical and intergenerational trauma is deeply rooted within us, and it cannot be erased. Yet, urging our children to be strong and resilient, to keep bouncing off these immovable boulders, is exhausting, frustrating, infuriating, and defeating. It can make us hard and angry as we keep colliding, never moving forward.9

Instead of instilling resilience, we should teach our children to be more like water. The spirit of water is free and flowing. It understands it cannot uproot or move the boulders, but its powerful, unapologetic and clever nature, flows around, left, right, or over the boulder, molding new paths for those who follow behind it. Water has the gentle power to erode the frame of the earth and carve out new, wider paths. Water has the intelligence of venerability and can change consistency. Water is not selfish, oppressive, or selective. It is a catalyst to help heal sicknesses. It is live giving to all the plant and animal relatives.9

Let us teach our Indigenous children to be less resilient and more purposeful like water—free, flowing with divine generosity, embodying healing and protection, embracing vulnerability and change. In thius way, they can transcend the weight of trauma, not rhgouh sheer endurance, but by creating new pathways of hope and strength for themselves and generations to come.”

“One finger cannot lift a pebble”

This wisdom is relevant when addressing ACEs. Overcoming the impacts of ACEs requires a collective effort from family, friends, educators, healthcare professionals, and the community. Just as a single finger cannot lift a pebble alone, a child cannot fully recover from trauma without a supportive network. This proverb highlights the necessity of community and teamwork in creating positive experiences and providing resources for children affected by ACEs.

Preventing ACEs in Indigenous communities involves promoting positive childhood experiences and supporting Indigenous children and families within their communities. Incorporating Indigenous frameworks, which include traditional healing practices, involving elders, and engaging the community, is very important for holistic healing. Building safe, stable, and nurturing relationships and environments for all Indigenous children is fundamental for their development. Strengthening community relationships, promoting cultural education and language, and creating an environment of belonging can significantly lessen the impact of ACEs. Additionally, providing access to healthcare, education, and social services tailored to the needs of Indigenous communities support overall well–being. Focusing on these protective factors, will help empower and inspire every Indigenous child to reach their full potential. This is a collective responsibility we all share.

Now, let’s dive deeper into this topic by checking out this video on preventing ACEs.10

Also, make sure to view the tabs below for more in-depth information on colonization, historical trauma, trauma risks, protective factors, current research, and more.

Last updated 11/01/24

The arrival of European colonizers in 1492 marked the beginning of significant upheaval for Indigenous communities. Understanding the historical context of colonization is important when addressing ACEs in Indigenous populations. The legacy of colonialism has established systemic challenges that contribute to the high prevalence of ACEs. According to Brockie et al., (2015) historical trauma stems from the loss of land, language and culture over the past century, coupled with ongoing discrimination, and continues to impact individuals who identify as AIAN today.1

To visualize this historical context, explore the interactive map created by University of Georgia historian Claudio Saunt.2 This map offers a time–lapse visualization of the transfer of Indian land between 1776 and 1887.2 As blue areas representing “Indian Homelands” fade away, small red sections emerge, illustrating the establishment of reservations.2

To understand how systems of oppression impact Indigenous peoples, here are some key terms to be familiar with, from an Indigenous perspective.

The U.S. Healthcare system was built, in part, on the erasure of Indigenous medicines and healing practices. Indigenous peoples regained their right to practice traditional medicine in 1978 through the American Indian Religious Freedom Act.10 The Indian Health Service (IHS) was established in 1955 to address health disparities and hospitals were built in Indian Country.11 Today, healthcare for Indigenous communities remains underfunded and inaccessible, which contributes to high rates of chronic diseases and mortality. However, many Tribal Nations are revitalizing traditional healing practices, which are holistic than Western medicine, often supporting the mind, body and spirit.12

Before colonization, Indigenous diets varied but were connected to the land, fish, game, and the three sisters (corn, beans, and squash).13 However, forced displacement and assimilation disrupted traditional practices of hunting, gathering, and farming, which lead to cultural loss, malnutrition, and starvation.13 The Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR) was introduced and authorized by the Food Stamp Act of 1977 to provide access to nutritious foods to low–income Native American households.14 Many of the food boxes contained high sodium, processed, and refined commodity items. Many indigenous peoples live in food deserts and in rural areas where they might spend half a day just making a grocery run.14 Getting to a place to purchase nutritious food becomes a constant struggle.

Indigenous communities face unique traumas that are often overlooked by standard ACEs screening tools. These tools typically focus on individual traumas like abuse and neglect but miss additional experiences unique to Indigenous people, such as the historical and intergenerational trauma.16 This trauma stems from colonization, forced assimilation, and systematic oppression that lead to cycles of trauma being passed down through generations.16

Historical trauma affects not just those who directly experienced it but also their descendants. This trauma continues to impact the mental and physical well–being of Indigenous communities, which contribute to higher rates of mental health challenges and substance misuse.16 Acknowledging this type of trauma is important when considering developing effective Indigenous wellness frameworks.

Watch this video of Leticia Aguilar, from the Pinoleville Pomo Nation and founder of Native Sister Circle, as she describes the interconnectedness of these terms.16

Another video on intergenerational trauma and its impact on Indigenous Australians.17

Check out this video from On Native Ground, a Hoopa Tribal non–profit media organization, on the impact of historical trauma, a Native perspective.18

On this page, we discuss the trauma, the risks, and protective factors that influence ACEs. ACEs are not caused by a single factor, but instead, a combination of factors at the individual, community, and societal levels. Factors at all levels are no child or individual’s fault. Let’s delve into the differences.

The word trauma means wound, shock, or injury that undermines a person’s sense of safety and creates a feeling that catastrophe could strike at any moment.1 Both children and adults are susceptible to trauma, which can manifest through shock, fear, anger, sadness, difficulty concentrating, and a sense of helplessness. Children may develop behavioral problems as a result.1 Active coping skills and strong support systems are important to alleviating symptoms and preventing the long–term effects of trauma on mental health.1

Trauma can be classified as acute, chronic, or complex, each with varying impacts on mental health.1 Long–term trauma can lead to emotional disturbances such as anger, anxiety, sadness, survivor’s guilt, post–traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and more.1

However, positive changes after trauma are possible when individuals acknowledge their difficulties and view themselves as survivors rather than victims.1 This can include building resilience, developing effective coping skills, and a sense of self–efficacy. Some people may redefine their relationships with new meaning and spiritual purpose and gain a deeper appreciation for life.1

Lateral violence within Indigenous communities occurs when those who have experienced oppression direct their frustrations towards fellow community members instead of their oppressors.2 This behavior creates an environment of toxic stress that affects Indigenous communities and intensifies the effects of historical trauma.2 Children exposed to such violence may suffer feelings of betrayal, isolation, low self–esteem, anxiety, and depression, which are components of ACEs.2 Lateral violence can manifest through bullying, social exclusion, nonverbal intimation, cyber–bullying, and physical violence. Addressing these issues promptly is beneficial for healing and resilience.2

Most Indigenous peoples experience complex and collective trauma due to historical and ongoing systemic discrimination, such as the legacy of boarding schools and forced assimilation policies.3 This trauma is not just a result of isolated incidents but a combination of factors at the individual, relationship, community, and societal levels that increase the risk of ACEs and violence.3

On top of this collective, historical, and intergenerational trauma that Indigenous peoples experience, there are also risk factors, which are characteristics that may increase the likelihood of experiencing ACEs.4 On the other hand, there are protective factors that decrease the likelihood of experiencing ACEs.4

Watch the Moving Forward5 video, from CDC, to learn more about how to lower ACEs and what is beneficial.

Individual and family risk factors include (to name a few):

Community risk factors include (to name a few):

Protective factors for individuals and families include:

Community protective factors include:

Check out this video on the effects of trauma on the body: ACEs: Impact on Brain, Body, and Behavior.6

Another video of ACEs and their Effects7

Recognizing these risks and protective factors are important for promoting well-being of Indigenous communities. Now, let’s look at how these factors can play out in real-life scenarios in the next tab.

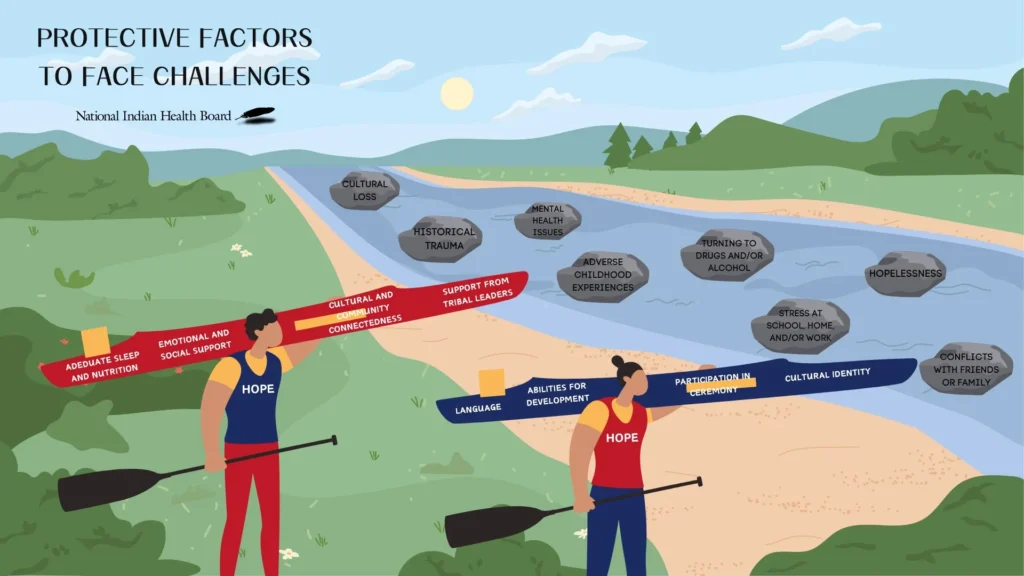

In this image, we see a river flowing and its waters are clear with big rocks. Along this river, two individuals prepare to embark on a journey in their kayaks. The river represents the path of life, and the rocks symbolize the challenges indigenous children experience, such as historical trauma, mental health issues, ACEs, and more.

The first individual is equipped with sleep, enough nutrition, and emotional and social support at home. He wears a t-shirt with the word, “hope,” symbolizing optimism he has cultivated in his life. These protective factors act as his paddle, helping him steer around the rocks, and help navigate the turbulent waters ahead. The second individual, wearing a red top, has learned his traditional ways, his language, and culture. These protective factors are also important to healing and understanding the community and environment. The outdoor environment, rich with natural beauty, reinforces the importance of connecting with nature and their indigenous roots.

As they paddle downstream, they learn to move like water, flowing around obstacles rather than being stopped by them. The combination of protective and cultural factors helps them navigate life’s adversities and allows them to be one with water—adaptable, renewed, and healthy. Together, they demonstrate that with the right support and connection to their community, nature, and self, they can overcome any challenges the river of life presents.

Two Feathers Native American Family Services (NAFS) is a light of hope and healing in Humboldt County, California. As a national leader in advancing Native mental health, Two Feathers NAFS employs innovative approaches that emphasize community building, honoring cultural identity, values, and traditions. Their mission is to address mental health challenges in geographically isolated and economically disadvantaged regions, and they envision a world filled with love and balance.1

They are dedicated to helping Native youth and their families achieve their full potential through culturally tailored mental health programs.

Chekws Counseling & Family Services is one of their cornerstone programs. It offers individual counseling, youth leadership programs, equine therapy, cultural programming, and intensive case management.1 These services are designed to strengthen family attachment, improve crisis management, reduce risk–taking behaviors, and enhance life skills. The program is built on a culturally responsive, trauma-informed framework that prioritizes access to cultural knowledge and addresses systemic inequities.1

The A.C.O.R.N. Youth Wellness Program focuses on teaching cultural values and their application to physical, mental, spiritual, and cultural aspects of daily life. The goal is to decrease trauma symptoms, improve relationships, and create a sense of hope through activities like inter–tribal drumming, song and dance, storytelling, art, basket–weaving, dress making, and trips to cultural events.1

Two Feathers NAFS is a trailblazer of how culturally tailored mental health services create profound and positive changes in Indigenous communities. Their dedication to honoring traditions while addressing modern challenges sets a powerful example for others to follow.

NIHB visited Two Feathers Native American Family Services to learn more about their programs. Two Feathers NAFS is a national leader in Native mental health advancement through a blend of innovative approaches that center community building and cultural affirmation to address long standing mental health challenges in Two Feathers’ geographically isolated and economically challenged region.

Here are photos from our site visit:

These videos provide a glimpse into the transformative power of their programs and the virbrant community they have built together. We hope their stories inspire and resonate with you.

For more information on Two Feathers NAFs, visit their website. You can also explore their YouTube channel to watch more videos on substance abuse prevention and their healing journeys.

The Desert Sage Youth Wellness Center in Hemet, California, is making a significant impact on the lives of AI/AN youths, ages 12-17, by providing culturally centered, individualized and evidence–based substance use disorder and behavioral health services.2 This residential treatment center creates a mental and spiritual health environment that meets the unique needs of the Indigenous communities it serves.2

Their mission is to offer substance use disorder treatment that is culturally relevant and tailored to everyone’s needs.2 Their vision is to provide a supportive environment that creates mental and spiritual well–being for AI/AN youth.2

They offer a range of services including residential treatment, behavioral health counseling, substance use counseling, individual and group counseling, family therapy, traditional healing services, traditional arts and crafts, field trips, educational opportunities, academic, and life–skills education.2

Desert Sage focuses on holistic wellness and addresses the underlying trauma that accompanies many indigenous youths.

Check out these photos of our site visit. Although they don’t show anyone because it is a brand–new facility.

Blessing Sage bundle

Foosball table

Federally funded Regional Treatment Centers help Native youth

Organizations like Two Feathers NAFS and Desert Sage Youth Wellness Center are making a profound impact on Native youth by addressing trauma and providing culturally tailored mental health services. By providing trauma-informed care and culturally relevant support, they will help Native youth navigate life’s challenges creating a sense of hope, well–being, and positive changes in Indigenous communities.

Creating positive experiences for Native youth is our goal. By ensuring a safe home where needs are met, maintaining routines, and organizing fun or educational activities where they can learn enhances positive experiences. These protective factors can lessen the negative effects of ACEs and promote healthy lives.

References

Radford et al., (2021) explored the impact of ACEs on the health and wellbeing of Indigenous populations in North America. They found that Indigenous peoples have higher ACE scores compared to non–Indigenous groups, which are linked to depression, substance use, and chronic pain.1 However, current research often overlooks the historical and social contexts of Indigenous communities, such as the effects of colonialism and boarding school experiences.1 While the ACE model helps explain health disparities, it doesn’t capture the full complexity of Indigenous experiences. Other studies have shown that spiritual activities and a strong sense of cultural identity are associated with positive mental health outcomes despite having ACEs.1

Edwards et al., (2023) found that a strong connection to Indigenous culture serves as a protective factor against ACEs.2 Indigenous children often experience multiple ACEs with an average of four ACEs in just six months.3 They also found that caregivers deeply rooted in their culture show a weaker correlation between their own ACEs and those of their children.2 This suggests that cultural identity, traditional practices, and values can help break cycles of trauma, although social support alone is less effective and more complex. Broader family and community dynamics may offer additional protection against ACEs.2

Rides At The Door & Shaw, (2023) emphasize the need for Indigenous communities to address historical and intergenerational trauma to heal effectively.3 They propose the Indigenous Wellness Pyramid Framework, which integrates individual, family, community, and societal levels. This framework respects Indigenous sovereignty and decision-making, and it considers Indigenous healing practices as legitimate as Western medicine.3 They believe the goal is not just to extend life expectancy but to make sure that elders contribute to intergenerational healing and community sovereignty.4 This long–term process requires community–wider mobilization and ongoing efforts to restore balance and wellness among Indigenous communities.3

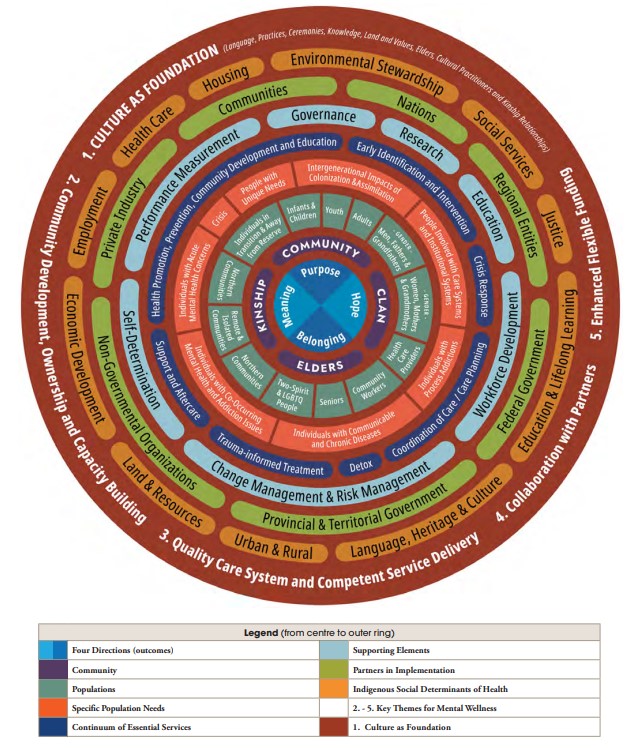

The First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum (FNMWC) is a framework designed for Indigenous peoples, grounded in culture, language, and traditional knowledge.4 It promotes holistic well–being by addressing mental and substance use challenges, while providing a roadmap for communities to enhance their mental wellness programs through collaboration and culturally appropriate health services tailored to their unique needs.4

The Historical Oppression, Resilience, and Transcendence Framework by Burnette and Figley (2017) offers a deeper understanding of how Indigenous communities demonstrate resilience in overcoming adversity.5 This framework focuses on the interconnectedness of mental, emotional, physical, and spiritual health and promotes a holistic approach to well–being. It also focuses on the development of protective factors, such as community support and cultural practices, which improve the capacity to cope with ACEs.5

The Indigenous Wellness Framework, created by the Thunderbird Partnership Foundation, focuses on cultural interventions delivered by knowledgeable Cultural Practitioners or Elders that impact the whole person—spirit, heart, mind, and body.6 The holistic approach creates a deep connection to one’s culture and promotes overall wellness.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSAs) Strategic Prevention Framework (SPF) offers a valuable approach for addressing high ACE scores. It provides a structured method for tackling substance misuse through five steps: Assessment, Capacity, Planning, Implementation, and Evaluation, while being guided by cultural competence and sustainability principles.7 However, this framework shouldn’t be used alone. Integrating it with an Indigenous framework or perspective can create a strategy that address both immediate and long-term needs that create well-being in Indigenous communities.

CDC’s Comprehensive Approach to Preventing ACEs uses multiple strategies derived from the best available evidence. These strategies focus on primary prevention but also include strategies to reduce long–term consequences of ACEs.8 The figure below highlights these areas. This approach may not incorporate the unique, cultural, historical and social contexts of Indigenous communities, especially the limited resources and poor infrastructure in remote and economically disadvantage areas of Indian Country. Without addressing these barriers, the strategies suggested may not reach those who need them most.

To further support these efforts, connecting Native youth to caring adults and activities, such as mentoring and after–school programs are beneficial. Having Indigenous approaches that involve the community, culture, and trauma–informed care can significantly improve health outcomes for those with a history of ACEs.

Check out CDC’s video on We Can Prevent ACEs9

|  |  |

| Module 1 Lesson 1: ACEs, Brain Development, and Toxic Stress 10 | Module 1 Lesson 2: The ACE Study 11 | Module 2 Lesson 1: ACEs 12 |

Disclaimer:

This resource was developed through the support from a cooperative agreement between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Indian Health Board (CDCOT18–1802, Grant #NU38OT000302). The findings and conclusions presented in this resource are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the U.S. government.

Here are some valuable tools from NIHB: Assessment Action Plan, Community Scan Action Plan, Action Plan, Implementation advice strategies, ACE Questionnaire, and additional questions for Indigenous communities. They are all available in the appendix section of this doc: https://acrobat.adobe.com/id/urn:aaid:sc:VA6C2:e9405e48-a9fc-4dcb-8a25-3fd1b4aa0386

Your donation directly supports our programs and services, providing high-quality resources and support to our community.

National Indian Health Board

50 F St NW, Suite 600

Washington, DC 20001

© 2024 National Indian Health Board